Edward Brown Thought Lost at Sea (PEO.25)

A memoir about the time Edward Brown was thought lost at sea

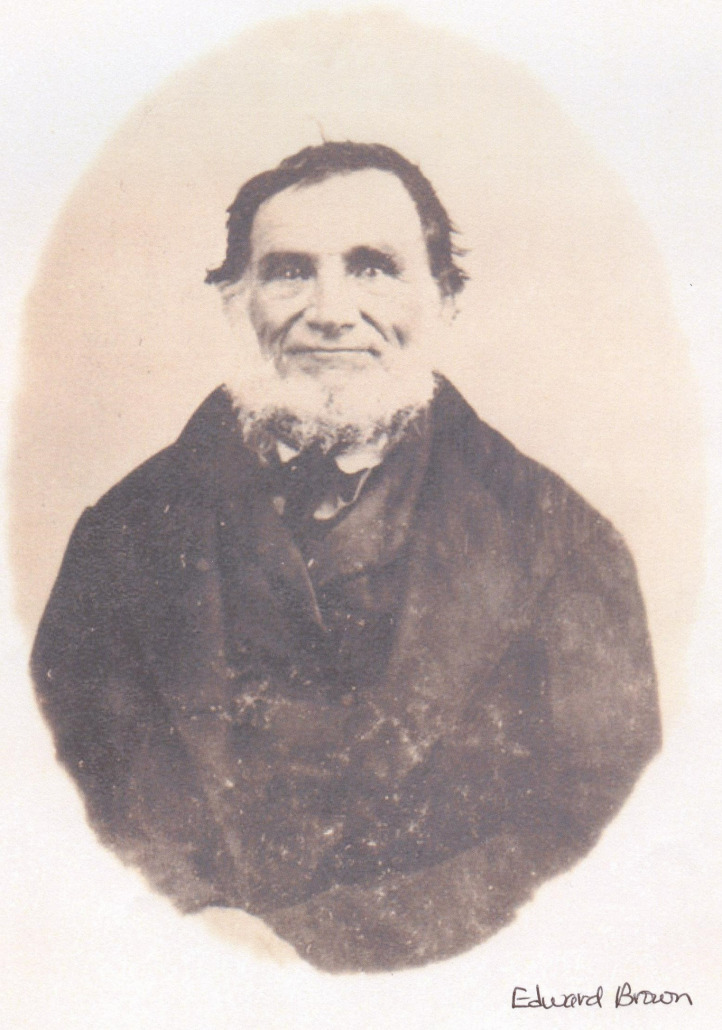

A brief biography of Edward Brown, said to have been born November 21, 1785 in Ipswich, Mass., is followed by the story of a time when he and his father-in-law Benjamin Billings were thought to be lost at sea. His wife Pamela, who gave birth to their child Martha Marks Brown while Edward was missing, was distraught. Her suffering, as well as her family’s attempts to comfort her, seem as real today as they did in 1819.

It is said that Edward was from Ipswich, Mass. but we don’t have Ipswich records to support that. Family records1 identify his parents as Edward and Mary Hapgood Brown and siblings George Wood, Mary and John. There is no family lore as to how and when he came to Sedgwick.

Edward married Pamela (Pamelia) Billings ( born 29 Jul 1797, Sedgwick) on 18 Nov 1818 and they had four children, Martha Marks (b. 07 Dec 1819), Salome (b. 17Jan 1825), Edward Henry (b. 29 Mar 1829) and Almira (b. 20 Feb 1835).

Edward is buried next to his wife Pamela in Settler’s Rest Cemetery in Sargentville and his gravestone is inscribed, “Edward Brown Born in Ipswich, Mass. Nov 21, 1785 Died in Sedgwick Dec 24 1865 80 years 1 mo”.

In his discussion of the War of 1812, Chatto writes, “Mr Edward Brown who later settled in Sedgwick, was another who saw hard service. From Ipswich, Mass., he went to sea at an early age and was impressed on a British man-o-war where he served six years, being under Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar. He escaped and fought the English from the deck of a Spanish warship, was once more impressed but, with the help of Abel Billings, a master mariner from Sedgwick, freed himself in the far away port of Malta and came into his own country. In 1812 he was on the sloop-of-war Frolic, which was captured by the enemy. Mr Brown was taken to Dartmoor prison and was there when the famous massacre of prisoners occurred.”2

Edward Brown Thought Lost at Sea

Written by Dora S. Currier, Sargentville, Nov. 5, 1922

Transcribed by Pamela Simmons 03/08/2013

The autumn weather of 1819 had been unusually severe, with storms and wind that swept the Atlantic and the coast of New England in a manner hitherto unknown to the few inhabitants settled along the shores of the beautiful Eggemoggin Reach. Some days, however, had been passing fair when little ripples broke softly on the ledges and isolated boulders at the shore of “Billings Cove” and the reddening leaves of the maples which bordered it fluttered slowly to the water’s edge. Where little children sailed their home-made boats along the smooth tide which bore its many shaded burdens now shoreward, and now outward, until they sunk swiftly out of sight. About Nov. 18 it so happened that Edward Brown and his father-in-law Benjamin Billings set out in a small vessel, of a build then quite common; with a high pointed stern and called a “pinkey”. Crops had not been large, money was scarce and a trip to Boston, with the prospect of picking up a load to bring back for “the folks” might be successful in bringing in some revenue to half feed the families thro the long winter so fast-approaching, for the slender stock of provisions brot from the village three miles away had run pitifully low.

For some days the winds were fair and the “Old Republic” held on her way and those on shore prophesised a good trip and aa safe return. Then suddenly followed storms of wind with blinding snow and fear gripped the heart of mother Abigail and daughter Pamela for those wise in the lore of the sea shook their heads and whispered, “Brown’s gone! Brown’s gone, there’s no doubt of it.” As week after week went by no word came and no familiar sail was seen rounding the “Point”. Then came one who had returned from a trip “up to the Westward” bringing news that the “Republic” had been wrecked on Cape Cod and Brown’s pea jacket had washed ashore with the vessels papers in the pocket. “Edward’s pea-jacket did not have any pockets in it” said Pamela tho her heart misgave her as she spoke.

On a cold December day there came to the home of Edward, a little stranger, and the mother lay in the one finished room and for days scarcely speaking, watched thro the window the sky and the foam caps on the dark water, and when the short, cold day was over and the tallow candle was lighted on the mantle, sadly she closed her eyes and listened, for he might come in the night and he must not find her sleeping. Sisters came and tried to rouse the young mother to some action but all she could say was “No Brown’s dead and I want to die. I shall not get up.” Then one bitter cold night-when the sun was setting over Sally Cove and the frosted grass crackled under the passing foot, sister Patience anxiously watching up the narrows, spied a small sail near Pumpkin Island and an inspiration came to her-and tying her woolen kerchief over her head she threw on a big shawll and with seeming confidence, hurried over to Pamela’s home. “Come Meela you must get up and have your bed made, and your clothes changed. Brown’s coming I saw the vessel just coming into the head of the Reach. You’ve got just time. I’ll help you.” And so Patience with a cheerful voice but with secret misgivings deftly dressed the mother and the baby Martha Marks and went home saying to herself “I’m afraid I told a wrong story perhaps it was Brown and perhaps not but something had to be done, and there was a little vessel coming into the narrows and she did look about as large as the Republic, tho they all think she has gone to the bottom long ago and Brown and father went with her. Meela must get up, may I be forgiven if I did wrong. I thot it was for the best. Well the Lord is good and I can say with the Psalmist, “tho he slay me yet will I trust in Him”.

Meantime the Republic for so it was in truth, came slowly round the Point. The anchor found its bed and the two lost no time in crossing the fields to reach home and find the “folks”. Pamela, nothing doubting, for hadn’t Patience said Brown was coming, slept not, but with wide-open eyes watched the moon-light thro the narrow windows, and guessed so near the time, that even as she thot to herself, “he must be coming now”, the door opened and Brown had come.

When the husband and wife had each told the other the story of the long weeks of separation, quiet again settled over the low-roofed gray house and father, mother and baby slep peacefully. Many years have passed since that night; all who were any way concerned in this story have passed to the Great Beyond. Kindly strangers have bot and improved the home where Edward and Pamela spent a long life. Only a few are left who knew them but those still remember them with loving thots and the old place holds a charm which will never belong to any other.

Dora S. Currier

It is told by the Martha of this sketch that when Benjamin Billings reached his home on that night, he looked thro the window and saw his wife Abigail asleep and by the light of the dying hearth-fire he could see her with one hand under her cheek dreaming of him perhaps, and with the thot-he sat down on the door stone and “cried like a little child”.

D.S.C.

Background information

Edward Brown was was 34 and Pamela Billings Brown 22 at the time of this story. They were married in Sedgwick 18 Nov 1818 and their daughter Martha Marks Brown was born 7 Dec 1819, while Edward and Benjamin were gone. Their other children were John, who died in infancy, Edward, Salome and Almira.

Patience Billings, the wife of Samuel Billings was Pamela’s sister. Their father was Benjamin Billings (born 12 Dec 1753) and their mother was Abigail Closson Billings (born 20 May 1757).

Martha Marks Brown, the baby referred to as “a little stranger” in this story. She married Abel Sawyer.

Addendum

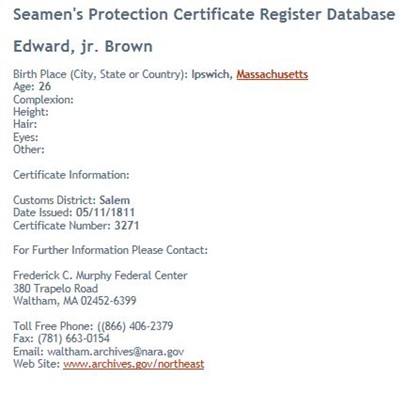

There are few early records related to Edward Brown but the following copy of Seamen’s Protection Certificate Number 3271 issued on 05/11/1811 to 28 year old Edward Brown Jr. born in Ipswich, Mass. may be one. The certificate entries reflect the date and place of birth inscribed on Edward’s gravestone and his designation as a “junior” is in line with the family belief that his father was also Edward Brown.

Seamen’s Protection Certificate Number 3271 issued on 05/11/1811 to 28 year old Edward Brown Jr. born in Ipswich, Mass.

The Seamen’s Protection Certificate Register Database web site describes the reason for the certificates:

In response to the impressment of American seamen by British ships, Comgress passed an “Act for the Relief and Protection of American Seamen” in 1796. The Act required customs collectors to maintain a record of all United States citizens serving on United States vessels. Each seaman, once registered with the customs collector, was given a Seaman’s Protection Certificate. These certificates vouched for the citizenship of the individual and included identifying information such as age, height, Complection, place of birth, and in some cases eye and hair color. The intention of these certificates was to discourage impressment. Although important documents it appears that seamen often misplaced theirs. At the very least there are several issued in consecutive years to what appear to be issued to the same person.3

______________________________

1 Dora S. Currier, Edward’s granddaughter

2 Chatto and Turner, Register of the Towns of Sedgwick, Brooklin, Deer Isle, Stonington and Isle Au Haut, 1910, Friend Memorial Public Library, Inc., Brooklin, Maine

3 http://library.mysticseaport.org/initiative/protectionindex.cfm